Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you. Help Now >

Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you. Help Now >

Converging and Convincing Proof of God: The Joy of Being

FREE Catholic Classes

As Aidan Nichols states in his book A Grammar of Consent, "Chesterton's writings contain what appears to be a novel argument for the existence of God. This argument may be termed the argument from joy." An argumentum e gaudio.

Highlights

Catholic Online (https://www.catholic.org)

12/4/2012 (1 decade ago)

Published in Year of Faith

Keywords: existence of God, proofs of God, joy, Chesterton, Andrew M. Greenwell, joie de vivre, joie d'etre

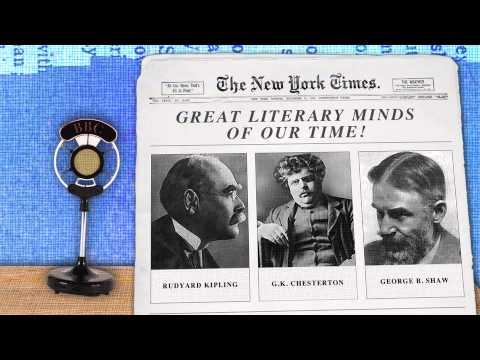

CORPUS CHRISTI, TX (Catholic Online) - Gilbert Keith Chesterton, with his leonine shock of hair, walrus-mustache, ample girth, his cigar in hand, and his ready and elfish grin, seems the most unlikely of men to turn to to find a proof for God's existence. But such a view would belie a lack of familiarity with the man. It would be to judge a book by its cover, and a natural philosopher by his clothes.

As Aidan Nichols states in his book A Grammar of Consent, "Chesterton's writings contain what appears to be a novel argument for the existence of God. This argument may be termed the argument from joy." An argumentum e gaudio.

For Chesterton, joy was the appropriate response to being--that everything, rather than nothing, is--and this experience of joy, and the gratitude it engenders, was a window into the transcendent.

As Chesterton saw it, joy was something more than mere happiness, more than mere the experience of pleasure. For him, in Aidan Nichols's words, "joy is the reaction to the fact that there should be such a thing as existence as such." Joy, the chara of the Scriptures, was, in Chesterton's eyes, a sort of cousin to the wonder, the thaumata, of the philosophers. This joy in existence as such contained "an implicit affirmation of the doctrine of creation, and hence of the truth of theism."

Chesterton noticed that joy is something that goes beyond science: science can describe it, but not fully answer the why of it. Science cannot tell us why there is being as such rather than no being at all. Chesterton observed that one could conclude from this either that joy has no meaning (which is hardly plausible) or (what is very probable) that joy had all the meaning in the world.

Now, Chesterton, who himself might have been called a dumb ox, was as philosophically astute as the original dumb ox, St. Thomas Aquinas. (One might recall here that the Thomist scholar Etienne Gilson considered Chesterton's biography on St. Thomas Aquinas "as being without possible comparison the best book ever written on St. Thomas.") Though philosophically astute, Chesterton did not in any way write a philosophical treatise on joy. His proof must therefore be distilled from his works-his essays, apologetical works, literary criticism, detective stories, plays, biographies, and verse--and his life.

Chesterton had a joie de vivre, a joy of living, but a lot of men, including pagans and Enlightenment philosophers, have that. Chesterton had something more than that: he also had a joie d'ĂŞtre, a joy of being. And it reflects itself in his works.

For example, in his poem Ballad of the White Horse, a ballad of the days of King Alfred, G. K. Chesterton has a passage where he refers to "joy without a cause." To understand the context, this phrase comes in a scene where the Blessed Virgin Mary comes to King Alfred the Great at the nadir of his struggle against the Danes:

Night shall be thrice night over you,

And heaven an iron cope.

Do you have joy without a cause,

Yea, faith without a hope?

The supernatural encounter with the Blessed Virgin Mary has its effect, and King Alfred goes to gather up his chiefs:

Up across windy wastes and up

Went Alfred over the shaws,

Shaken of the joy of giants,

The joy without a cause.

. . . .

And he set to rhyme his ale-measures,

And he sang aloud his laws,

Because of the joy of the giants,

The joy without a cause.

This joy has no earthly cause; hence, it is "without a cause." The earth is the wrong place to find it. This means that one who searches for its cause must open out into the infinite, upon He that is without cause: God, the Great Uncaused. For Chesterton, the existence of God was the only thing that rendered his joie d'ĂŞtre intelligible.

As Chesterton framed it in his novel The Poet and the Lunatics:

"Man is creature; all his happiness consists in being a creature; or, as the Great Voice commanded us, in being a child. All his fun is in having a gift or present; which the child, with profound understanding, values because it is a 'surprise.' But surprise implies that a thing came from outside ourselves; and gratitude that it comes from someone other than ourselves."

Gift. Joy. Thanks. Those are Chesterton's three themes that underlie his joie d'ĂŞtre.

Chesterton knew that there is an intimate connection between the experience of joy and the experience of grace or gift. One might say that he recognized that the experience of joy is a natural analogue of supernatural grace. It is not coincidence that the Greek word for joy--chara--is linguistically related to the Greek word for grace--charis--and the Greek word for giving thanks--eucharisto.

In his biography of St. Francis of Assisi, Chesterton links joy with the mystic's awareness that being was not something that could be taken for granted, but that being is a gift that God brought out of nothing. A mystic like St. Francis beholds, as he sees God and nothing else, the "the beginningless beginnings in which there was really nothing else" but God. He then appreciates not only "everything," but also the "nothing of which everything was made."

Everything is a gift brought out from nothing, ex nihilo, by God the Creator of all things. The mystic is, as it were, brought to the time "when the foundations of the world are laid," and there he joins "with the morning stars singing together and the sons of God shouting for joy" and expresses a spiritual joie d'ĂŞtre. Thank God--He that is--that He included us in his to be!

In Chesterton's book Orthodoxy, one encounters a fully-developed philosophy of joy which is capped with a theology of joy.

For Chesterton, the modern philosophies were absolutely wrong because of their sorrow. "The modern philosopher had told me again and again that I was in the right place, and I still felt depressed even in acquiescence."

Certainly one of those modern philosophers was Nietzsche who had a horrible fault, Chesterton thought. And that was his inability to laugh. The best he could do was sneer. This, certainly Chesterton must have believed, arose from Nietzsche's inability to appreciate the common things of life, in particular that most common thing we share with all creation: being. No wonder Nietzsche thought God was dead! Nietzsche had no joie d'ĂŞtre, and it drove him to philosophical insanity.

Chesterton would not let the modern philosophers get him down. He had heard another report. "But I had heard that I was in the wrong place," he says in Orthodoxy, "and my soul sang for joy like a bird in spring."

Wrong place? What did Chesterton mean?

What Chesterton meant is that for all the joie de vivre we find on earth, in the temporal life, the earth is not the right place to look for the joie d'ĂŞtre. Every thing was the "wrong place," as the right place was where there was no thing from which every thing came to be. It is at the interstice between Creator and created where we get our joie d'ĂŞtre. If there is no Creator, then being is not a gift, and there is no joy in it, and there is no possible One to whom we can give thanks.

Chesterton saw that the experience of joy at the very thought that there was being rather than nothing, found its perfect answer, its supernatural companion in the Christian faith and in the Gospels.

Grace--supernatural joy--built on nature--natural joy. Joie de la grâce built on joie d'être. It was a perfect fit.

"Man is more himself, man is more manlike, when joy is the fundamental thing in him, and grief the superficial . . . . . praise should be the permanent pulsation of the soul. . . . . Joy ought to be expansive . . . . Christianity satisfies suddenly and perfectly man's ancestral instinct for being the right way up; satisfies it supremely in this; that by its creed joy becomes something gigantic and sadness something special and small. . . . . Joy, which was the small publicity of the pagan, is the gigantic secret of the Christian."

In the book Conversations with Kafka by Gustav Janouch, the morose Kafka commented on reading Chesterton's Orthodoxy and The Man who was Thursday: "Er ist so lustig, dass man fast glauben könnte, er habe Gott gefunden." "He is so joyful, that one might almost believe that he had found God."

Yes, Kafka was right. Chesterton had found God, and then he had found Jesus and His Church, and all this through joy, an inerrant guide. He found Him first naturally in the joie d'être which seemed to escape the melancholy Kafka. He found Him yet again, in a higher key, in the joie de la grâce of the Gospels and the Catholic Faith.

As Cardinal Ratzinger--himself a fan of Chesterton--put it in his book Light of the World, "My life has always been traversed by this conviction: it is Christianity that gives joy and makes it grow." Pope Benedict XVI reminds us in his most recent book that the Gospel story begins with the angel Gabriel's salutation to Mary (often translated as "Hail"), but which is better rendered as: Rejoice! (Luke 1:28: chaire)

Chesterton's life was nothing but an incarnation of one phrase in St. Paul's epistle to the Philippians: "Rejoice in the Lord always. I will say it again: Rejoice!" (Phil. 4:4)

Gift. Joy. Thanks. What a way to live!

-----

Andrew M. Greenwell is an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas, practicing in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is married with three children. He maintains a blog entirely devoted to the natural law called Lex Christianorum. You can contact Andrew at agreenwell@harris-greenwell.com.

---

'Help Give every Student and Teacher FREE resources for a world-class Moral Catholic Education'

Copyright 2021 - Distributed by Catholic Online

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

An Urgent Message from Sister Sara – Please Watch

- Advent / Christmas

- 7 Morning Prayers

- Mysteries of the Rosary

- Litany of the Bl. Virgin Mary

- Popular Saints

- Popular Prayers

- Female Saints

- Saint Feast Days by Month

- Stations of the Cross

- St. Francis of Assisi

- St. Michael the Archangel

- The Apostles' Creed

- Unfailing Prayer to St. Anthony

- Pray the Rosary

![]()

Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2025 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.